HOLLYWOOD - Looking up Vine Street from Hollywood Boulevard the sudden rise of the street just above Yucca St. on the hill where The Hollywood Freeway lays atop shows the not so subtle signs of The Hollywood Fault, which has been in the news lately. Recent mapping by the California Geological Survey shows the fault is what helps give Hollywood and Los Feliz its character with its hills, and while the beauty is nice some developers are none too happy with this study.

When The Hollywood Fault, or any Southern California fault, will rupture with fury again is not clear as there are no accurate ways to predict earthquakes (not to be confused with forecasting earthquakes).

Walking over and along The Hollywood Fault on Los Feliz Blvd. one wonders about earthquakes past, and thus this piece is not about unhappy developers not getting their way, or even so much The Hollywood Fault, but rather five odd, peculiar Southern California earthquake facts.

Severe freeway damage following the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake. Used under a Creative Commons license.

1 - The First Earthquake on Record

For thousands and thousands of years earthquakes, both very small and very large, have been happening in Southern California, as paleoseismology has proven, but while there were many animals and trees to feel the shaking as hills and mountains were being pushed up there were hardly many humans around. Any humans that were around never kept anything written about it, or hid their diary.

It would not be until 1769 that the first earthquake in Southern California would be recorded. Gaspar de Portola, Father Juan Crespí and a group of over 60 explorers from Spain, in the name to extend Spain's control up the Pacific Coast and establish colonies and missions (and hopefully prevent Russia and England from acquiring and taking this territory), set out from San Diego to Monterey on July 14, 1769. Maps at the time available to de Portola's group showed California extending from San Diego only to the Monterey Bay.

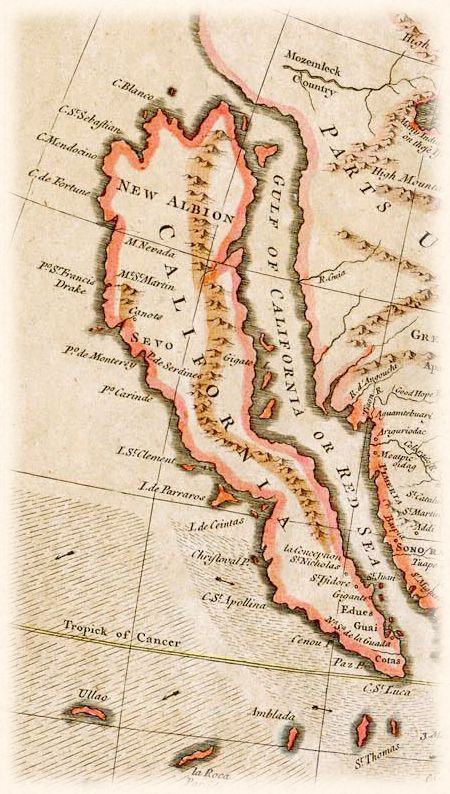

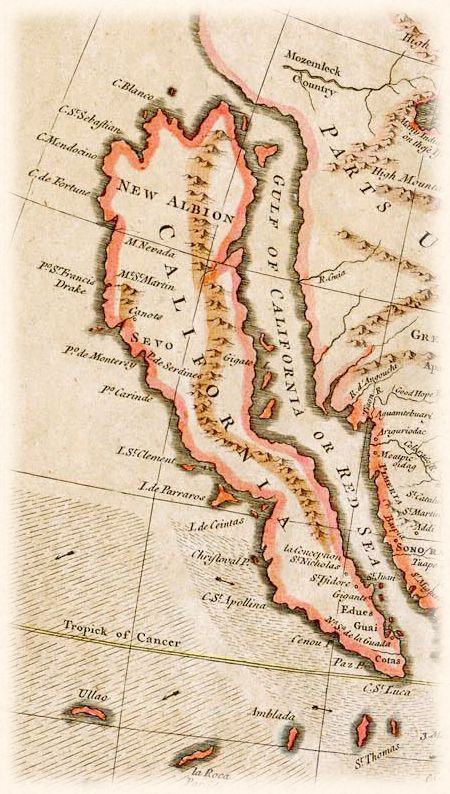

When California was still thought of as an island in this 1745 map of California, and so not unusual to think de Portola's group thought the soon-to-be Golden State went as far as Monterey. Used under Creative Commons license.

After about a couple weeks of walking from San Diego to current day Orange County on July 28, 1769 and setting up camp at what is now The Santa Ana River in Anaheim de Portola's group felt a very large earthquake.

This earthquake occurred around 4 p.m., and the explorers recorded many aftershocks, several of them strong, as they made their way into the San Gabriel Valley. Records kept by de Portola's group show they stopped feeling any earthquakes when they were exiting the San Fernando Valley.

Among geologists, seismologists and historians there is much debate on just how big this earthquake was and just where the epicenter was located. Given the records by the de Portola team it was believed by many in the science and historic communities this earthquake was around magnitude 6.0 and probably on The San Jacinto Fault in the Inland Empire. Part of this was based on the diaries of the de Portola team saying they felt no more earthquakes once exiting the San Fernando Valley.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) officially lists this earthquake, the very first earthquake in a long, forever growing list of Southern California earthquakes cataloged by the USGS, as M6.0 in the Los Angeles Basin.

The when and where of this first recorded Southern California earthquake by the USGS has been challenged by University of California-Irvine geology professor Lisa Grant. Ms. Grant has proposed that the 1769 earthquake was actually M7.3 located on the relatively unknown San Joaquin Hills Fault located between Newport Beach and Laguna Beach, which resulted in the Orange County coastline being raised by almost 11 feet.

Put together by The Southern California Earthquake Center here is a scenario of a M6.7 earthquake on The San Joaquin Hills Fault.

The video above, combined with the diaries kept by the de Portola team, shows the theory by the UCI professor to be possible as strong shaking wanes in The San Fernando Valley. One thing the debate of the 1769 earthquake has brought up is the fact that Orange County has a major earthquake fault line that is not really well known, which has brought on more studies of the fault.

The when and where of this very first recorded Southern California earthquake still fascinates geologists and seismologists. Among other reasons, figuring out the mystery of this earthquake may help further understand and clarify the nature of earthquakes in Southern California (like the existence of a major earthquake fault in Orange County).

2 - Last Large Earthquake on Record

The last large earthquake in Southern California was a M7.9 in 1857, which is commonly called The Fort Tejon Earthquake. Not only was this the largest earthquake in Southern California recorded history, but this was one the largest earthquakes ever recorded in the United States.

This was also the last time The San Andreas Fault had a major rupture in Southern California. The infamous fault line is believed to have ruptured near Parkfield and continued rupturing south to just near The Cajon Pass. In fact, this was the last time "The Big One" happened in Southern California.

Southern California was nowhere near the megalopolis it is today, and so damage was limited to scars in the Earth. There were many scares in the Earth with cracks reported in the San Gabriel Valley and in the San Bernardino area.

In some areas the shaking is believed to have lasted up to, and even over three minutes. In Downtown L.A. the shaking is believed to have lasted over a minute.

Both the USGS and disaster planners fear the impact a repeat of this earthquake would have today.

The last time the lower southern segment of the San Andreas Fault between San Bernardino to the Salton Sea ruptured is believed to have been in or around 1690.

3 - Deadliest Earthquake Ever

The earthquake was only M6.4, but the deadliest earthquake in Southern California was the March 1933 Long Beach Earthquake, which killed 120 people. Much of the death was due to the brick construction of many buildings in Long Beach and Compton.

Compton in the aftermath of the 1933 earthquake. The fallen bricks are what killed many people in this earthquake. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Many schools were badly damaged, but luckily school was out when the earthquake struck at 5:55 p.m. (which should break the myth that big earthquakes only happen in the morning). Had this earthquake occurred just a few hours earlier the death toll would have been much higher with many school children killed.

This thought disturbed and worried a lot of people, and very quickly in April 1933 the state passed The Field Act that mandated earthquake resistant construction for schools.

Jefferson Junior High School in Long Beach after the quake. Damage to schools like this throughout the area and what could have been worried parents, teachers and students alike, which led to the passage of The Field Act. Used under a Creative Commons license.

In the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake schools built after The Field Act made it through with no damage while schools built before 1933 suffered major damage.

A newsreel showing the aftermath of the 1933 earthquake.

4 - The 1933 Epicenter Was NOT in Long Beach

The deadly jolt in 1933 will forever be known as The Long Beach Earthquake, but the epicenter was not in Long Beach. Rather, the epicenter was in Newport Beach on The Newport-Inglewood Fault.

While the damage was bad in Long Beach the earthquake ended up being the most damaging and deadliest earthquake in Orange County history. Most of the death and destruction was in Santa Ana. However there was also major damage in Garden Grove and Anaheim.

Very badly damaged building in Santa Ana. Used under Creative Commons license.

Damage was so bad in downtown Santa Ana that the Santa Ana Register, which was located in downtown Santa Ana, put together their newspaper working outside of their damaged building.

Of course this would not be the first time an epicenter would be misidentified. The Sylmar Earthquake was not in Sylmar, but the hills above Sylmar. The Northridge Earthquake was not in Northridge, but in Reseda.

5 - The Christmas Day Earthquake

If you were asleep on Christmas morning in 1899 and felt the house shake you may have thought it was Santa Claus stuck in your chimney trying to wiggle his way out. It was not Santa, but Mother Nature showing that even big earthquakes do not get the holiday off.

At 4:25 a.m. a M6.5 earthquake stuck near San Jacinto on the fault of the same name, The San Jacinto Fault.

This earthquake was felt in a very wide area waking people up in Los Angeles, San Diego and as far as Santa Barbara.

Damage was greatest in San Jacinto and Hemet with many collapsed buildings. In Riverside many chimneys were knocked down and cracks in many buildings appeared. In fact, throughout much of the then sparsely populated Inland Empire the damage reports were much the same along with shattered windows.

The earthquake was deadly at the nearby Soboba Indian Reservation, where six people were killed by falling adobe walls.

In the Earth sciences community there is a little bit of debate if whether this earthquake was larger than M6.5 and just where exactly the epicenter was located. The Southern California Earthquake Center believes the epicenter may have been ten miles south of San Jacinto.

In the end, whether an earthquake hits on Christmas morning or during an imperialistic exploration journey, it is extraordinarily important to be prepared for the next big earthquake.

When The Hollywood Fault, or any Southern California fault, will rupture with fury again is not clear as there are no accurate ways to predict earthquakes (not to be confused with forecasting earthquakes).

Walking over and along The Hollywood Fault on Los Feliz Blvd. one wonders about earthquakes past, and thus this piece is not about unhappy developers not getting their way, or even so much The Hollywood Fault, but rather five odd, peculiar Southern California earthquake facts.

Severe freeway damage following the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake. Used under a Creative Commons license.

1 - The First Earthquake on Record

For thousands and thousands of years earthquakes, both very small and very large, have been happening in Southern California, as paleoseismology has proven, but while there were many animals and trees to feel the shaking as hills and mountains were being pushed up there were hardly many humans around. Any humans that were around never kept anything written about it, or hid their diary.

It would not be until 1769 that the first earthquake in Southern California would be recorded. Gaspar de Portola, Father Juan Crespí and a group of over 60 explorers from Spain, in the name to extend Spain's control up the Pacific Coast and establish colonies and missions (and hopefully prevent Russia and England from acquiring and taking this territory), set out from San Diego to Monterey on July 14, 1769. Maps at the time available to de Portola's group showed California extending from San Diego only to the Monterey Bay.

When California was still thought of as an island in this 1745 map of California, and so not unusual to think de Portola's group thought the soon-to-be Golden State went as far as Monterey. Used under Creative Commons license.

After about a couple weeks of walking from San Diego to current day Orange County on July 28, 1769 and setting up camp at what is now The Santa Ana River in Anaheim de Portola's group felt a very large earthquake.

This earthquake occurred around 4 p.m., and the explorers recorded many aftershocks, several of them strong, as they made their way into the San Gabriel Valley. Records kept by de Portola's group show they stopped feeling any earthquakes when they were exiting the San Fernando Valley.

Among geologists, seismologists and historians there is much debate on just how big this earthquake was and just where the epicenter was located. Given the records by the de Portola team it was believed by many in the science and historic communities this earthquake was around magnitude 6.0 and probably on The San Jacinto Fault in the Inland Empire. Part of this was based on the diaries of the de Portola team saying they felt no more earthquakes once exiting the San Fernando Valley.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) officially lists this earthquake, the very first earthquake in a long, forever growing list of Southern California earthquakes cataloged by the USGS, as M6.0 in the Los Angeles Basin.

The when and where of this first recorded Southern California earthquake by the USGS has been challenged by University of California-Irvine geology professor Lisa Grant. Ms. Grant has proposed that the 1769 earthquake was actually M7.3 located on the relatively unknown San Joaquin Hills Fault located between Newport Beach and Laguna Beach, which resulted in the Orange County coastline being raised by almost 11 feet.

Put together by The Southern California Earthquake Center here is a scenario of a M6.7 earthquake on The San Joaquin Hills Fault.

The video above, combined with the diaries kept by the de Portola team, shows the theory by the UCI professor to be possible as strong shaking wanes in The San Fernando Valley. One thing the debate of the 1769 earthquake has brought up is the fact that Orange County has a major earthquake fault line that is not really well known, which has brought on more studies of the fault.

The when and where of this very first recorded Southern California earthquake still fascinates geologists and seismologists. Among other reasons, figuring out the mystery of this earthquake may help further understand and clarify the nature of earthquakes in Southern California (like the existence of a major earthquake fault in Orange County).

2 - Last Large Earthquake on Record

The last large earthquake in Southern California was a M7.9 in 1857, which is commonly called The Fort Tejon Earthquake. Not only was this the largest earthquake in Southern California recorded history, but this was one the largest earthquakes ever recorded in the United States.

This was also the last time The San Andreas Fault had a major rupture in Southern California. The infamous fault line is believed to have ruptured near Parkfield and continued rupturing south to just near The Cajon Pass. In fact, this was the last time "The Big One" happened in Southern California.

Southern California was nowhere near the megalopolis it is today, and so damage was limited to scars in the Earth. There were many scares in the Earth with cracks reported in the San Gabriel Valley and in the San Bernardino area.

In some areas the shaking is believed to have lasted up to, and even over three minutes. In Downtown L.A. the shaking is believed to have lasted over a minute.

Both the USGS and disaster planners fear the impact a repeat of this earthquake would have today.

The last time the lower southern segment of the San Andreas Fault between San Bernardino to the Salton Sea ruptured is believed to have been in or around 1690.

3 - Deadliest Earthquake Ever

The earthquake was only M6.4, but the deadliest earthquake in Southern California was the March 1933 Long Beach Earthquake, which killed 120 people. Much of the death was due to the brick construction of many buildings in Long Beach and Compton.

Compton in the aftermath of the 1933 earthquake. The fallen bricks are what killed many people in this earthquake. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Many schools were badly damaged, but luckily school was out when the earthquake struck at 5:55 p.m. (which should break the myth that big earthquakes only happen in the morning). Had this earthquake occurred just a few hours earlier the death toll would have been much higher with many school children killed.

This thought disturbed and worried a lot of people, and very quickly in April 1933 the state passed The Field Act that mandated earthquake resistant construction for schools.

Jefferson Junior High School in Long Beach after the quake. Damage to schools like this throughout the area and what could have been worried parents, teachers and students alike, which led to the passage of The Field Act. Used under a Creative Commons license.

In the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake schools built after The Field Act made it through with no damage while schools built before 1933 suffered major damage.

A newsreel showing the aftermath of the 1933 earthquake.

4 - The 1933 Epicenter Was NOT in Long Beach

The deadly jolt in 1933 will forever be known as The Long Beach Earthquake, but the epicenter was not in Long Beach. Rather, the epicenter was in Newport Beach on The Newport-Inglewood Fault.

While the damage was bad in Long Beach the earthquake ended up being the most damaging and deadliest earthquake in Orange County history. Most of the death and destruction was in Santa Ana. However there was also major damage in Garden Grove and Anaheim.

Very badly damaged building in Santa Ana. Used under Creative Commons license.

Damage was so bad in downtown Santa Ana that the Santa Ana Register, which was located in downtown Santa Ana, put together their newspaper working outside of their damaged building.

Of course this would not be the first time an epicenter would be misidentified. The Sylmar Earthquake was not in Sylmar, but the hills above Sylmar. The Northridge Earthquake was not in Northridge, but in Reseda.

5 - The Christmas Day Earthquake

If you were asleep on Christmas morning in 1899 and felt the house shake you may have thought it was Santa Claus stuck in your chimney trying to wiggle his way out. It was not Santa, but Mother Nature showing that even big earthquakes do not get the holiday off.

At 4:25 a.m. a M6.5 earthquake stuck near San Jacinto on the fault of the same name, The San Jacinto Fault.

This earthquake was felt in a very wide area waking people up in Los Angeles, San Diego and as far as Santa Barbara.

Damage was greatest in San Jacinto and Hemet with many collapsed buildings. In Riverside many chimneys were knocked down and cracks in many buildings appeared. In fact, throughout much of the then sparsely populated Inland Empire the damage reports were much the same along with shattered windows.

The earthquake was deadly at the nearby Soboba Indian Reservation, where six people were killed by falling adobe walls.

In the Earth sciences community there is a little bit of debate if whether this earthquake was larger than M6.5 and just where exactly the epicenter was located. The Southern California Earthquake Center believes the epicenter may have been ten miles south of San Jacinto.

In the end, whether an earthquake hits on Christmas morning or during an imperialistic exploration journey, it is extraordinarily important to be prepared for the next big earthquake.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete$9 Million Fraud Judgment Against Antony Gordon In Federal Court

ReplyDeleteThis fraud judgment has led to Antony Gordon’s Chapter Seven bankruptcy, which is a straight liquidation.

This (2:13-ap-01536-DS 1568931 Ontario Ltd., an Ontario (Canada Corporati v. Gordon et al) looks like a $9 million dollar fraud judgment in federal court against Rabbi Chanan (Antony) Gordon (an attorney, motivational speaker, and hedge fund manager).

http://www.lukeford.net/blog/?p=59030

Két sắt,

ReplyDeleteđá hoa cương cao cấp,

đá ốp lát,

đá granite,

Quần áo bảo hộ lao động,

Giầy bảo hộ lao động ,

Mũ bảo hộ lao động,

Kính bảo hộ lao động,

Áo phản quang,

Áo phông đồng phục,